description:

The intrepid Robert X. Cringely leads us on another adventure, this time delving into the history of the Internet. Nerds 2.0.1 is the sequel to his first special, Triumph of the Nerds.

episodes:

Invention is rarely the isolated product of a lone scientist or engineer. Instead, every significant technology in the modern world is the product of a long history of numerous people and events. One of our most modern inventions, the Internet, is itself the result of decades of work and innovation by thousands of people who may have never dreamed of the possibility or potential of a global network.

One interesting and influential ancestor in the history of the Internet is radar. Hundreds of the best scientists and engineers in Britain and the U.S. worked during World War Two to develop radar systems to help them to defeat the Axis powers. Electronics technology was pushed to new heights to make the signals stronger, and early computing machines were developed to process the complex radar messages.

In the 50’s and 60’s, the Cold War spurred further research in radar and computers . The U.S. government feared that the Russians were pushing ahead of the west in science and technology, and the launch of the Russian Sputnik symbolized a new era and a new frontier. A call to arms swelled university campuses with budding scientists and engineers ready to burn their slide rules and retake the lead in technology from the Communists.

The U.S. government poured hundreds of millions of dollars into research and it was a golden age for R&D around the country. New federal agencies, such as NASA and ARPA, were created to distribute the research money around . MIT especially benefited from the Cold War, building new labs and hiring the best nerds in the country to work in them. High-tech companies sprang up around MIT, staffed with MIT graduates. One of these companies, Bolt, Barenek and Newman (BBN), would take the lead in developing the ARPAnet, the forerunner to the Internet.

The ARPAnet began as a government program thought up in the halls of the Pentagon. BBN was paid to build the connecting hardware and software, and several universities funded by ARPA were chosen to test the network. In 1969, only four computers were connected to the ARPAnet, but it grew and advances in computer technology made it faster and easier to use. Better networking protocols and applications were developed, especially email, and more people were convinced that it was going to be a success.

At the beginning of 1989 over 80,000 host computers were connected to what was now called the Internet. That same year, after some solemn thought, the aging ARPAnet was turned off signaling a transfer of the Internet from the hands of the Nerds to the Suits.

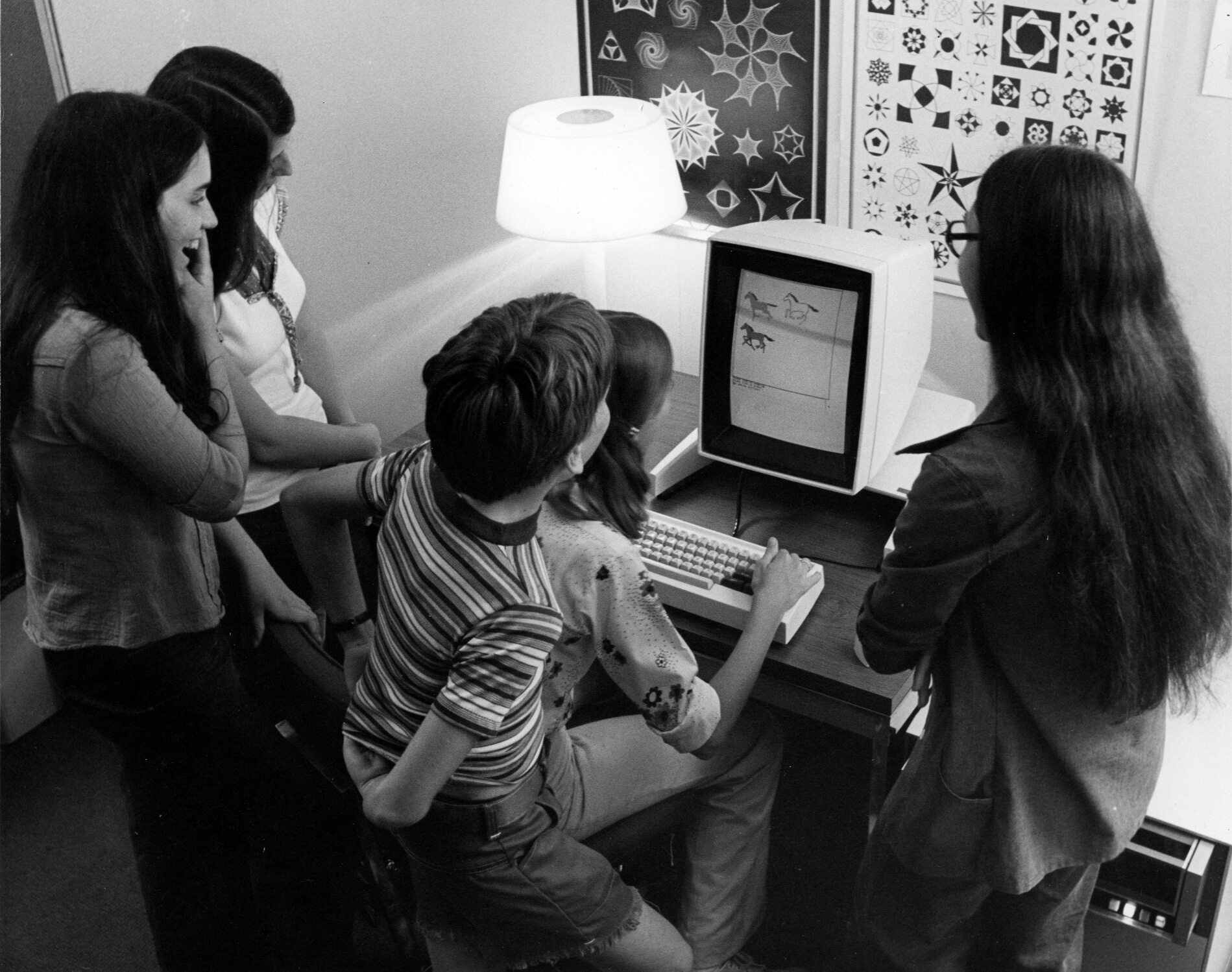

The rise of the personal computer by Apple and IBM introduced the rest of the world to computing. At first, computers were the tools of technically inclined nerds, but new applications drew other people to the keyboard. With an affordable modem, people could connect with other computer enthusiasts and commercial online services. People were using the computer as Bush and Licklider had prophesized, as a medium to interact with other people.

A venerable institution of international collaboration was the setting for the major development in the history of the Internet. It began when Tim Berners-Lee, a computer programmer at CERN in Switzerland, got to play on a new NeXT workstation. The object-oriented operating system was an inspiration for a problem he was working on – how to distribute information across a diverse network of different computers and operating systems. He started working on a protocol very similar the “docuverse” described by Ted Nelson, but reduced it down to a minimal, working model.

Berners-Lee eventually named his project the World Wide Web, because he visualized it as a web of interconnected documents that would stretch across the Internet and the world. It sounded grandiose, but his predictions were later proven too low.

In 1992, Marc Andreessen, an undergraduate computer science major at the University of Illinois, was working at the Super Computer Center when he discovered Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web. There were a few sites scattered around the world, including the first U.S. site at the Stanford Linear Accelerator, but it was hard to use. Marc and some of the other programmers knew they were looking at a great idea with a bad presentation. They wanted to put a more “human face” on the Web, so they wrote the first graphical browser – later to become Netscape.

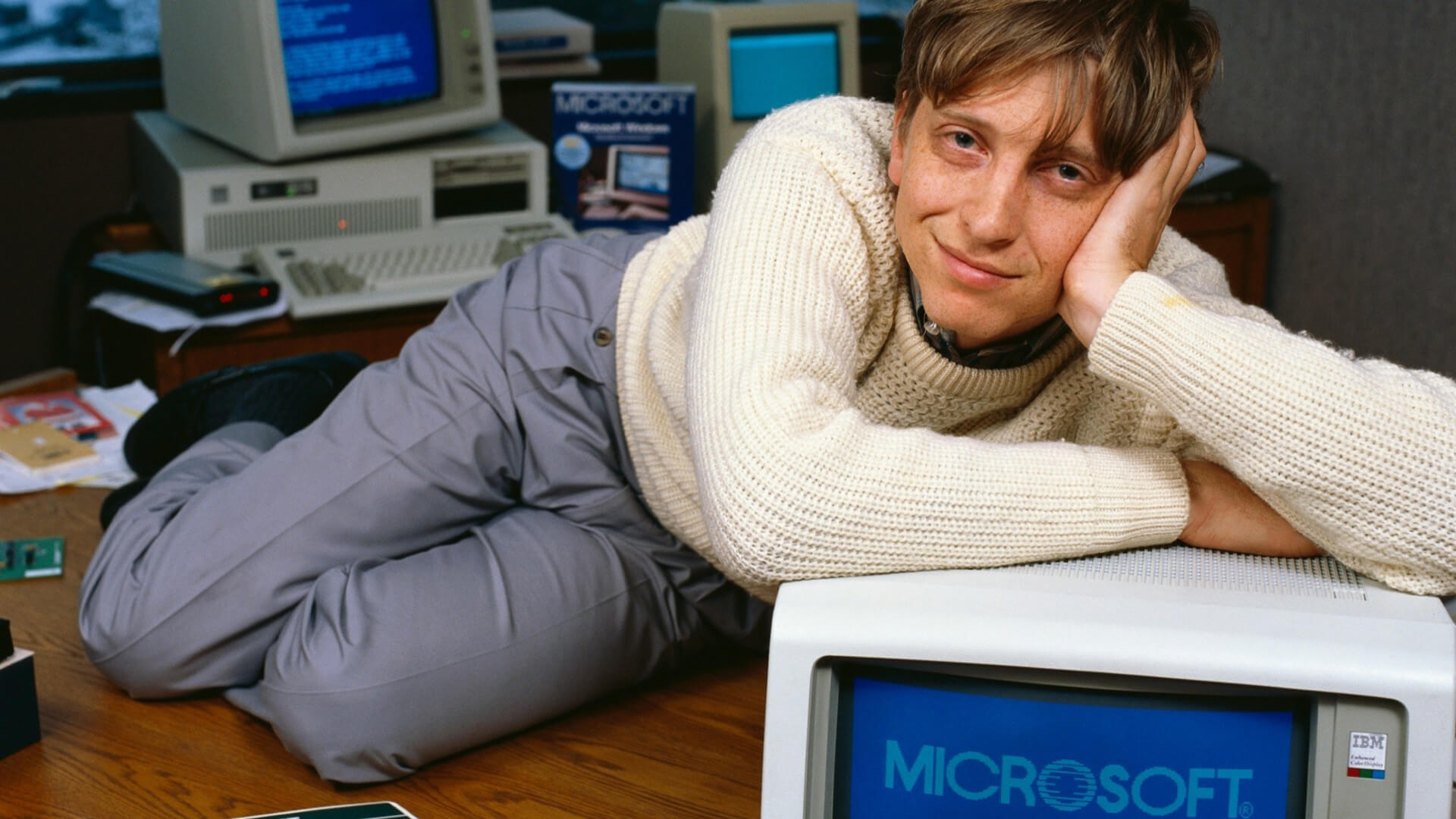

Microsoft saw no profit in the Internet, because there were specific laws against any profits on the Net. However, when Rep. Frederick Boucher from Virginia drafted a bill in the U.S. Congress that would change all that. Soon, the Internet was open for business.

Microsoft finally jumped onto the Internet in 1995, offering a browser to compete with Netscape – a browser they called Internet Explorer. It looked like the giant from Redmond, Washington would take over the Internet just as they took over the OS market – but the competition called foul.

After 1995, every business was at least thinking about getting a Web site. Online services exploded when they offered connections to the Internet and the World Wide Web. Traffic on the Internet was increasing at an exponential rate, and the old network backbones were showing signs of collapse. Some of the ARPAnet pioneers were predicting a collapse if something wasn’t done soon.

In the 1980’s, personal computers became a common fixture in homes and offices. Supplying business with computers and software grew into one of the biggest industries in less than a decade. Soon, networking became a profitable business for engineers previously restricted to networking mainframes.

Some of the engineers trained on the ARPAnet went out on their own to found some of the fastest growing high-tech companies in history. Bob Metcalfe, one of the pioneers of ARPAnet, developed a better way of networking personal computers together and founded 3Com.

Four 27 year-olds from Stanford and Berkeley formed a company named Sun and built networkable workstations that could crunch numbers faster than many mainframes. Taking advantage of Metcalfe’s invention, four programmers in Utah wrote a network operating system (Netware) and resurrected Novell Systems into a multi-billion dollar software company. A married couple working at Stanford developed an improved way to connect different networks together and operated a multi-million dollar company, named Cisco, from their house until venture capitalists took over and propelled it to a multi-billion dollar business.