description:

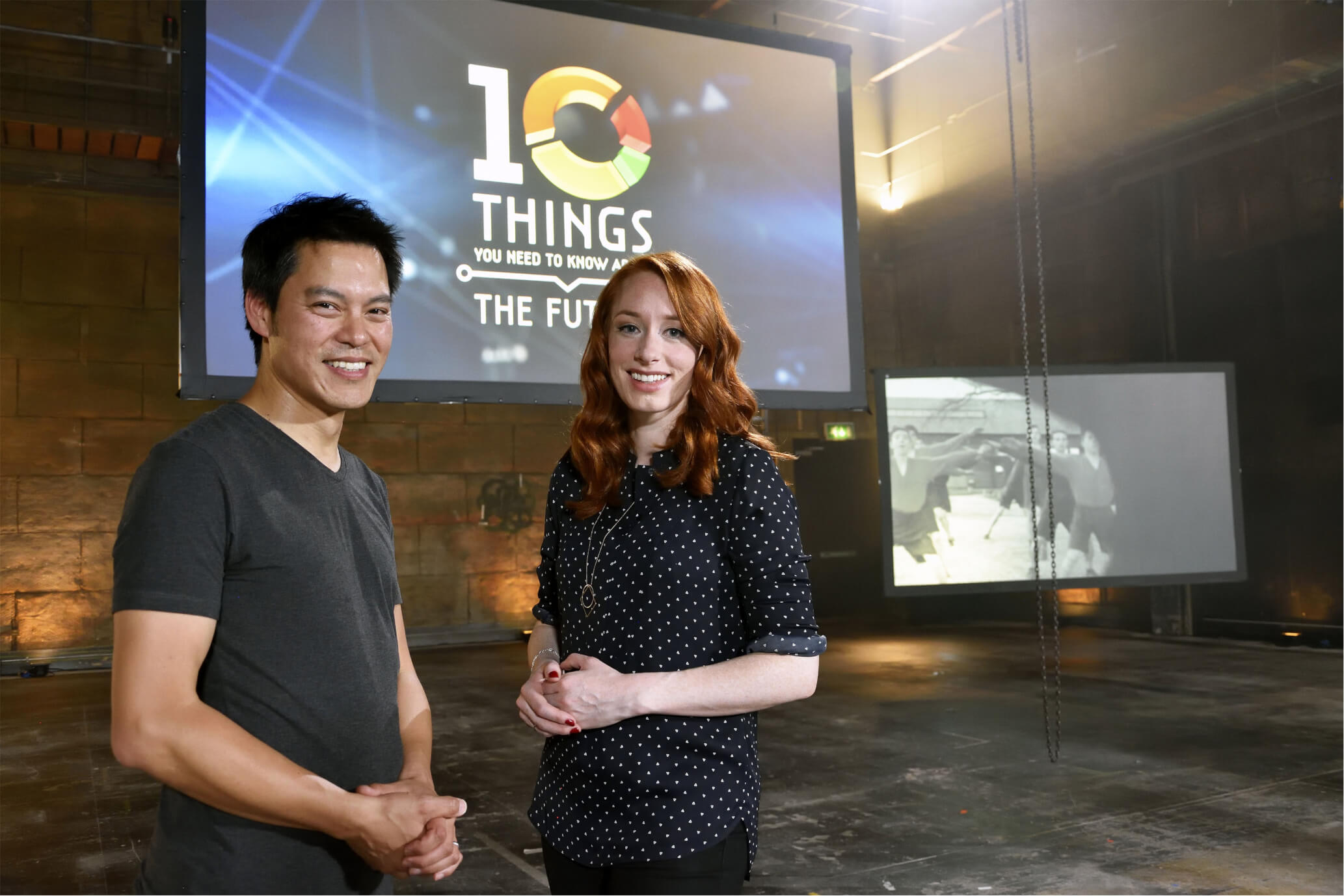

Victorian Sensations transports us to the thrilling era of the 1890s. Dr Hannah Fry, Paul McGann, and Philippa Perry explore a decade of rapid change that still resonates today.

episodes:

Victorian Sensations transports us to the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign to explore a moment of thrilling discovery and change that continues to resonate today.

In the first of three films focusing on the technology, art and culture of the 1890s, mathematician Dr Hannah Fry explores how the latest innovations, including X-rays, safety bicycles, and proto-aeroplanes, transformed society and promised a cleaner, brighter and more egalitarian future.

Whereas Victorian progress in the 19th century had been powered by steam and gas, the end of the 1800s marked the beginning of a new ‘Electric Age’. Hannah discovers how electrical energy dominated the zeitgeist, with medical quacks marketing battery-powered miracle cures, and America’s new electric chair inspiring stage magicians to electrify their illusions. The future had arrived, courtesy of underground trains and trams (as well as electric cars), and in the 1890s the first houses built specifically with electricity in mind were constructed.

Like our own time, there was concern about where this technology would lead and who was in control. HG Wells warned of bio-terrorism, while the skies were increasingly seen as a future battleground, fuelling the race to develop powered flight.

Hannah outlines the excitement around the coming Electric Age. Electricity was a signifier of modernity and Hannah discovers how electric light not only redefined the way we saw ourselves but changed what we expected from our homes. The new enthusiasm for all things electric was also something exploited by canny entrepreneurs. In the 1890s many believed that electricity was life itself and that nervous energy could be recharged like a battery.

In 1896, out of nowhere, the X-ray arrived in Britain. Hannah delves into the story of what Victorians considered to be a superhuman power. This cutting-edge technology was a smash hit with the public who found the ghoulish ability to peer under flesh endlessly entertaining. In the medical profession, X-rays caused a revolution and, as well as changing our views of our bodies, the X-ray revealed new fears in society about personal privacy and control over technology – concerns that sound very familiar today.

Electricity ruled the imagination, but it was a simple mechanical device that brought the greatest challenge to the social order: the safety bicycle. It offered freedom on a scale unimagined before and, for women of the time in particular, a new independence, changes to their clothes to make cycling easier and the opportunity for a chance encounter with a member of the opposite sex. But there was also a darker side, with fears of how technology might be turned against us becoming a constant fear in contemporary 1890s fiction.

One technological landmark that the Victorians knew was coming, and that they (rightly) anticipated would one day unleash fire and bombs on British cities, was the flying machine. A thing of fantasy yet also, due to the ingenuity of the age’s engineers, something that might become a reality at any moment. Leading the way for British hopes of achieving powered flight was Percy Pilcher. Hannah looks at how, after several successful flights, Pilcher designed a triplane with an engine he intended to fly, when disaster struck.

The 1890s was the decade when science, entertainment, art and morality collided – and the Victorians had to make sense of it all. Actor Paul McGann discovers how the works of HG Wells, Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde were shaped by fears of moral, social and racial degeneration.

Paul, seated in Wells’s time machine, sees how the author’s prophecies of a future in which humanity has decayed and degenerated highlighted the fears of the British Empire. Paul finds out how these anxieties were informed by new scientific theories based on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Paul learns how Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton sought to improve the genetic stock of the nation, through a project he coined as ‘eugenics’.

Another of the decade’s prominent scientific thinkers – Austrian physician Max Nordau – declared that it was art and culture, and their practitioners – the aesthetes and decadents – that were causing Britain’s moral degeneration, singling out Oscar Wilde as the chief corrupting influence. Paul explains how Wilde sought to subvert traditional Victorian values. Tucked away in one of Wilde’s haunts – the famous Cheshire Cheese Pub on Fleet Street – Paul hears from Stephen Calloway about how Aubrey Beardsley – the most decadent artist of the period – scandalised society, in much the same way as Wilde, through his erotic drawings. Wilde and Beardsley were not alone in being parodied by Punch Magazine. Historian Angelique Richardson shows Paul caricatures of a new figure who had begun to worry the sensibilities of Victorian Britain. Known collectively as The New Woman, this was a group of female writers, who in more than 100 novels, portrayed a radical new idea of femininity that challenged the conventions of marriage and motherhood. However, as Paul discovers through reading a short story called Eugenia by novelist Sarah Grand, some advocated the idea of eugenics through their writing.

For eugenicists, if one means of keeping a ‘degenerate’ working class in check was incarceration, then that either meant prison or, increasingly by the 1890s, the asylum. Some lost their freedom due to ‘hereditary influence’, others to so-called sexual transgression. Paul explains how the ‘vice’ of masturbation was seen as sapping the vitality of the nation. The idea of sexual transgression was to intrude into the Victorian consciousness as never before when, in 1895, Oscar Wilde was found guilty of gross indecency and sentenced to two years in jail.

While Oscar Wilde had made a very public show of defiance, Paul uncovers another leading – and gay – writer of the period, John Addington Symonds, who together with the prominent physician Havelock Ellis, sought to produce a scientific survey of homosexuality. At the London Library, Symonds expert Amber Regis shows Symonds’s rare handwritten memoirs to Paul, which served as a source for the groundbreaking 1897 work, Sexual Inversion. Paul explains how questions of sex and gender also lie at the heart of a very different book, published in the same year – Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Paul explains how Stoker had his finger – or teeth – on the pulse of the 1890s, infusing his novel with many of the decade’s chief preoccupations and growing fears of racial prejudice and immigration.

Paul also meets Natty Mark Samuels (founder of the Oxford African School) reciting a speech by a young West Indian called Celestine Edwards, who took a brave stand against imperial rule and its racist underpinnings. Edwards became the first black editor in Britain, and his pioneering work would be continued by a fellow West Indian, Henry Sylvester Williams, who in 1897 formed the African Association. Outside the former Westminster Town Hall, Paul describes how, in 1900, Williams set up the first Pan-African Conference to promote and protect the interests of all subjects claiming African descent.

In the final episode of this series, psychotherapist Philippa Perry time-travels back to the 1890s to explore how the late Victorian passion for science co-existed with a deeply held belief in the paranormal. Using a collection of rare and restored Victorian films from the BFI National Archive, she shows how the latest media innovations made use of contemporary ideas of ghosts and the afterlife – and how this ‘new media’ anticipated today’s networked world.

The final years of Queen Victoria’s reign were a moment when the old Victorian order rubbed shoulders with the beginnings of our modern world. It was a chaotic, febrile time of discovery and innovation in science and technology, entertainment and art, and the Victorians had to make sense of it all.

Philippa finds out how Marconi’s early experiments with wireless telegraphy encouraged speculation amongst the public and scientists that telepathy – communication between minds – would be the next scientific breakthrough. She also replicates eminent physicist Oliver Lodge’s pioneering experiment with radio waves and discovers his fascination for exploring the paranormal with the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). This Victorian group of ghost hunters included William James, a pioneer of psychology, biologist Alfred Russel Wallace and even Prime Minister William Gladstone. Buried in the archives of the SPR in Cambridge University Library, Philippa finds an incredible Census of Hallucinations that contains 17,000 ghostly encounters sourced from the Victorian public.

Maybe it’s not surprising that people of the age saw so many ghosts because, in a sense, spirits did haunt the Victorian home. Every Victorian innovation – from photography to motion pictures, phonographs to fantasy books – had its own supernatural genre. Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the hyper-rational Sherlock Holmes, drew on his real-life experience as a ghostbuster to write his ghostly fiction. Philippa learns the art of spirit photography from Almudena Romero and poses for her own ghostly picture as well as exploring a rare private collection of phonographs, the recent craze that allowed Victorians to hear communications from the past and listen to their loved ones after their deaths for the first time.

Philippa also explores the impact of the arrival in 1896 of motion pictures, the decade’s greatest and most magical media innovation. BFI curator Bryony Dixon shows her restored Victorian trick films, from the funny and feminist to a disturbing fake execution. Philippa then creates her own homage to the Big Swallow trick film and eats the cameraman.

The boundary between fact and fantasy was often blurred, and sensationalism infused the new tabloid journalism. At Cambridge University’s Institute of Astronomy, Philippa learns about other forms of long-distance communication and the flurry of press interest in stories from Mars. Dr Joshua Nall reveals that some of the greatest public figures of the decade, from Nikola Tesla to Sir Francis Galton, were convinced that signalling with Martians was possible. HG Wells’s story The Crystal Egg takes up this theme and predicts future media developments and the power of communications. And even Queen Victoria herself took advantage of the globally networked world that was emerging to allow the film cameras in to capture her triumphant Diamond Jubilee procession for all her imperial subjects. The jubilee was the first global mass media event and the footage captures the essence of the 1890s: the old Victorian order with an empire and an empress, rubbing shoulders with a world we recognise – a modern one of film cameras and global communications. This was the decade the future landed.