description:

Race is one topic where we all think we’re experts. Yet ask 10 people to define race or name “the races,” and you’re likely to get 10 different answers. Few issues are characterized by more contradictory assumptions and myths, each voiced with absolute certainty.

In producing this series, we felt it was important to go back to first principles and ask, What is this thing called “race?” – a question so basic it is rarely raised. What we discovered is that most of our common assumptions about race – for instance, that the world’s people can be divided biologically along racial lines – are wrong. Yet the consequences of racism are very real.

How do we make sense of these two seeming contradictions? Our hope is that this series can help us all navigate through our myths and misconceptions, and scrutinize some of the assumptions we take for granted. In that sense, the real subject of the film is not so much race but the viewer, or more precisely, the notions about race we all hold.

We hope this series can help clear away the biological underbrush and leave starkly visible the underlying social, economic, and political conditions that disproportionately channel advantages and opportunities to white people. Perhaps then we can shift the conversation from discussing diversity and respecting cultural difference to building a more just and equitable society.

episodes:

Everyone can tell a Nubian from a Norwegian, so why not divide people into different races? That’s the question explored in “The Difference Between Us,” the first hour of the series. This episode shows that despite what we’ve always believed, the world’s peoples simply don’t come bundled into distinct biological groups. We begin by following a dozen students, including Black athletes and Asian string players, who sequence and compare their own DNA to see who is more genetically similar. The results surprise the students and the viewer, when they discover their closest genetic matches are as likely to be with people from other “races” as their own.

Much of the program is devoted to understanding why. We look at several scientific discoveries that illustrate why humans cannot be subdivided into races and how there isn’t a single characteristic, trait – or even one gene – that can be used to distinguish all members of one race from all members of another.

HUMAN VARIATION

Modern humans – all of us – emerged in Africa about 150,000 to 200,000 years ago. Bands of humans began migrating out of Africa only about 70,000 years ago. As we spread across the globe, populations continually bumped into one another and mixed their mates and genes. As a species, we’re simply too young and too intermixed to have evolved into separate races or subspecies.

So what about the obvious physical differences we see between people? A closer look helps us understand patterns of human variation:

In a virtual “walk” from the equator to northern Europe, we see that visual characteristics vary gradually and continuously from one population to the next. There are no boundaries, so how can we draw a line between where one race ends and another begins?

We also learn that most traits – whether skin color, hair texture or blood group – are influenced by separate genes and thus inherited independently one from the other. Having one trait does not necessarily imply the existence of others. Racial profiling is as inaccurate on the genetic level as it is on the New Jersey Turnpike.

We also learn that many of our visual characteristics, like different skin colors, appear to have evolved recently, after we left Africa, but the traits we care about – intelligence, musical ability, physical aptitude – are much older, and thus common to all populations. Geneticists have discovered that 85% of all genetic variants can be found within any local population, regardless of whether they’re Poles, Hmong or Fulani. Skin color really is only skin deep. Beneath the skin, we are one of the most similar of all species.

Certainly a few gene forms are more common in some populations than others, such as those controlling skin color and inherited diseases like Tay Sachs and sickle cell. But are these markers of “race?” They reflect ancestry, but as our DNA experiment shows us, that’s not the same thing as race. The mutation that causes sickle cell, we learn, was passed on because it conferred resistance to malaria. It is found among people whose ancestors came from parts of the world where malaria was common: central and western Africa, Turkey, India, Greece, Sicily and even Portugal – but not southern Africa.

CONFRONTING OUR MYTHS ABOUT RACE

We have a long history of searching for innate differences to explain disparities in group outcomes – not just for inherited diseases, but also SAT scores and athletic performance. In contrast to today’s myth of innate Black athletic superiority, a hundred years ago many whites felt that Black people were inherently sickly and destined to die out. That’s because disease and mortality rates were high among African Americans – the cause was poverty, poor sanitation, and Jim Crow segregation, but it was easier for most people to believe it was a result of “natural” infirmity, a view popularized by influential statistician Frederick Hoffman in his 1896 study, Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro.

Racial beliefs have always been tied to social ideas and policy. After all, if differences between groups are natural, then nothing can or should be done to correct for unequal outcomes. Scientific literature of the late 19th and early 20th century explicitly championed such a view, and many prominent scientists devoted countless hours to documenting racial differences and promoting man’s natural hierarchy.

Although today such ideas are outmoded, it is still popular to believe in innate racial traits rather than look elsewhere to explain group differences. We all know the myths and stereotypes – natural Black athletic superiority, musical ability among Asians – but are they really true on a biological level? If not, why do we continue to believe them? Race may not be biological, but it is still a powerful social idea with real consequences for people’s lives.

It’s true that race has always been with us, right? Wrong. Ancient peoples stigmatized “others” on the grounds of language, custom, class, and especially religion, but they did not sort people according to physical differences. It turns out that the concept of race is a recent invention, only a few hundred years old, and the history and evolution of the idea are deeply tied to the development of the U.S.

“The Story We Tell” traces the origins of the racial idea to the European conquest of the New World and to the American slave system – the first ever where all the slaves shared similar physical traits and a common ancestry. Historian James Horton points out that the enslavement of Africans was opportunistic, not based on beliefs about inferiority: “[Our forebears] found what they considered an endless labor supply. People who could be readily identified and so when they ran away they couldn’t melt into the population like Native Americans could. People who knew how to grow tobacco, people who knew how to grow rice. They found the ideal, from their standpoint, the ideal labor source.”

Ironically, it was not slavery but freedom – the revolutionary new idea of liberty and the natural rights of man – that led to an ideology of white supremacy. Historian Robin D.G. Kelley points out the conundrum that faced our founders: “The problem that they had to figure out is how can we promote liberty, freedom, democracy on the one hand, and a system of slavery and exploitation of people who are non-white on the other?” Horton illuminates the story that helped reconcile that contradiction: “And the way you do that is to say, ‘Yeah, but you know there is something different about these people. This whole business of inalienable rights, that’s fine, but it only applies to certain people.’” It was not a coincidence that the apostle of freedom himself, Thomas Jefferson, also a slaveholder, was the first American public figure to articulate a theory speculating upon the “natural” inferiority of Africans.

Similar logic rationalized the taking of American Indian lands. When the “civilized” Cherokee were forcibly removed from their homes in Georgia to west of the Mississippi, one in four died along the way, in what became known as The Trail of Tears. President Andrew Jackson defended Indian removal: it was not the greed of white settlers that drove the policy, but the inevitable fate of an inferior people established “in the midst of a superior race.”

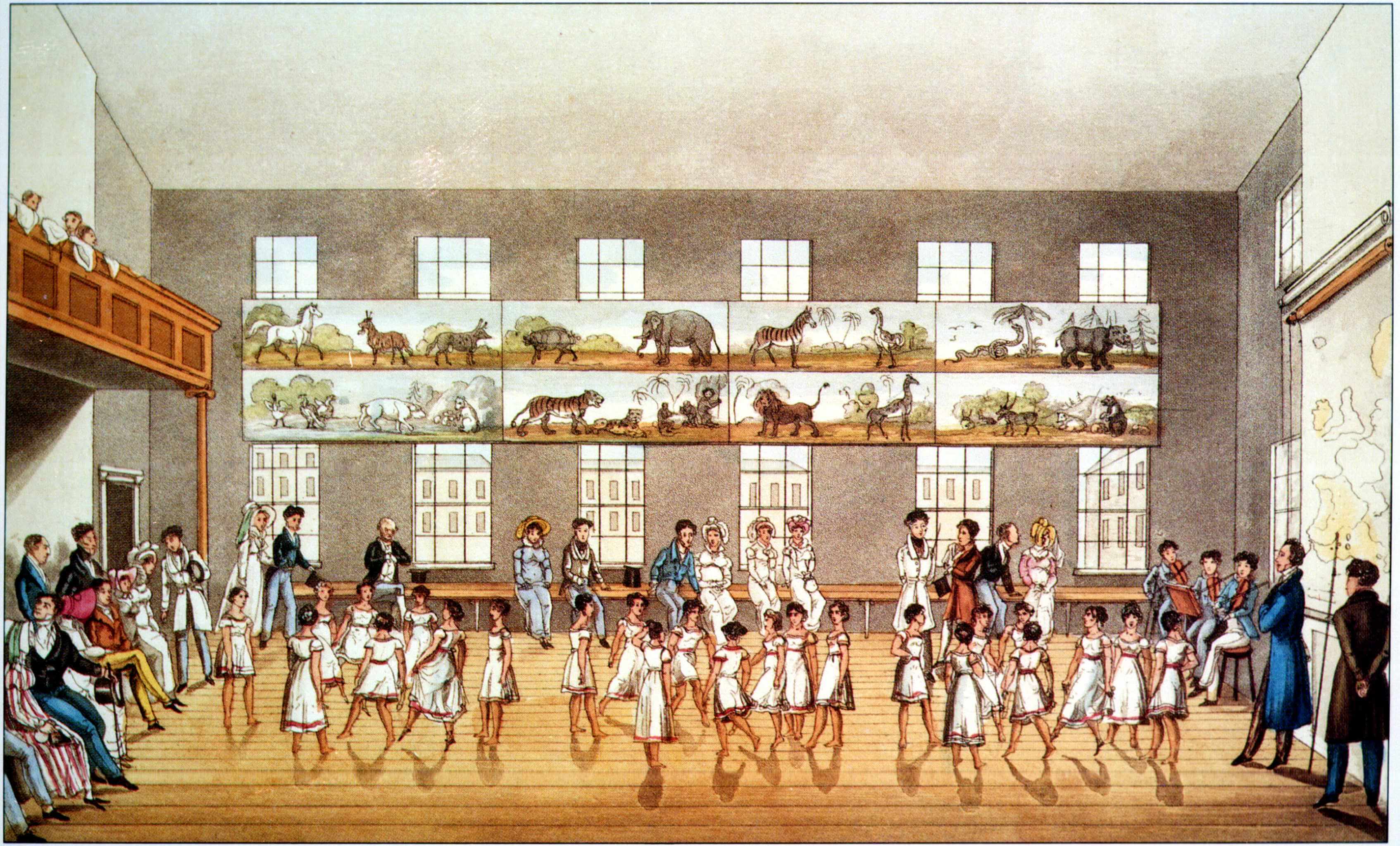

By the mid-19th century, race had become the accepted, “common-sense” wisdom of white America, explaining everything from individual behavior to the fate of human societies. The idea found fruition in racial science, Manifest Destiny, and our imperial adventures abroad. In the new monthly magazines of the late 19th century and at the remarkable indigenous people displays at the 1904 World’s Fair celebrating the centennial of Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, we see how American popular culture reinforced and fueled racial explanations for American progress and power, imprinting ideas of racial difference and white superiority deeply into our minds.

“The Story We Tell” is an eye-opening tale of how deep social inequalities came to be rationalized as natural – deflecting attention from the social practices and public policies that benefited whites at the expense of others.

If race doesn’t exist biologically, what is it? And why should it matter? Our final episode, “The House We Live In,” is the first film about race to focus not on individual attitudes and behavior but on the ways our institutions and policies advantage some groups at the expense of others. Its subject is the “unmarked” race: white people. We see how benefits quietly and often invisibly accrue to white people, not necessarily because of merit or hard work, but because of the racialized nature of our laws, courts, customs, and perhaps most pertinently, housing.

The film begins by looking at the massive immigration from eastern and southern Europe early in the 20th century. Italians, Hebrews, Greeks and other ethnics were considered by many to be separate races. Their “whiteness” had to be won. But who was white? The 1790 Naturalization Act had limited naturalized citizenship to “free, white persons.” Many new arrivals petitioned the courts to be legally designated white in order to gain citizenship. Armenians, known as “Asiatic Turks,” succeeded with the help of anthropologist Franz Boas, who testified on their behalf as an expert scientific witness.

In 1922, Takao Ozawa, a Japanese immigrant who had attended the University of California, also appealed the rejection of his citizenship application. He argued that his skin was physically white and that race shouldn’t matter for citizenship. The Supreme Court, however, decided that the Japanese were not legally white based on science, which classified them as Mongoloid rather than Caucasian. Less than a year later, in the case of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the court contradicted itself by concluding that Asian Indians were not legally white, even though science classified them as Caucasian. Refuting its own reasoning in Ozawa, the justices declared that whiteness should be based not on science, but on “the common understanding of the white man.”

Next we see how Italians, Jews and other European ethnics fared better, especially after World War II, when segregated suburbs like Levittown popped up around the country, built with the help of new federal policies and funding. Real estate practices and federal government regulations directed government-guaranteed loans to white homeowners and kept non-whites out, allowing those once previously considered “not quite white” to blend together and reap the advantages of whiteness, including the accumulation of equity and wealth as their homes increased in value. Those on the other side of the color line were denied the same opportunities for asset accumulation and upward mobility.

Today, the net worth of the average Black family is about 1/8 that of the average white family. Much of that difference derives from the value of the family’s residence. Houses in predominantly white areas sell for much more than those in Black, Hispanic or integrated neighborhoods, and so power, wealth, and advantage – or the lack of it – are passed down from parent to child. Wealth isn’t just luxury or profit; it’s the starting point for the next generation.

How does the wealth gap translate into performance differences? New studies reveal that when the “family wealth gap” between African Americans and whites is taken into account, there is no difference in test scores, graduation rates, welfare usage and other measures. It’s a lack of opportunities, not natural differences, that’s responsible for continuing inequality. Wealth, more than any other measure, shows the accumulated impact of past discrimination, and shapes your life chances.

“Colorblind” policies which ignore race only perpetuate these inequities. As Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun wrote, “To get beyond racism we must first take account of race. There is no other way.” As The House We Live In shows us, until we address the legacy of past discrimination and confront the historical meanings of race, the dream of equality will remain out of reach.