There’s no better illustration of scientific debates over the rise of humans than the story of how Ramapithecus was cast out of our ancestry. In this first lecture, witness how fossil evidence and molecular evidence—working both together and independently—can help explain some of anthropology’s most complex issues.

One of the most famous scientific debates in anthropology took place in the 1970s, with the discovery of fossil remains of a possible Homo ancestor, Australopithecus afarensis. Where exactly did Homo come from? Follow this highly public story from the perspective of the key personalities involved: scientists Don Johanson and Richard Leakey.

In 1994, paleontologists discovered the 4.4-million-year-old remains of Ardipithecus ramidus. Is it a true hominin? What skeletal features suggest the tradeoffs between being an effective climber and walking bipedally? Answer these and other questions by closely examining the fossil and genetic evidence of this fascinating “ground ape.”

Your brain separates you more from apes than any other anatomical feature. Investigate the gradual increase in hominid brain size in the fossil record. Looking at what fossil skulls (such as the Taung skull) reveal about blood circulation and cooling, you’ll shed new light on brain size and skull structure.

Explore the relationship between diet and morphology in this lecture on Australopithecus robustus and Australopithecus africanus. The teeth and jaws of these two species, you’ll discover, offer intriguing windows into the fierce debate surrounding the dietary hypothesis and the true adaptive differences between robust and gracile hominids.

Was Africa or Asia more central to human origins? How can we tell? Drawing on the ideas and theories of prominent scientists, including Charles Darwin, Ernst Haeckel, and Louis Leakey, learn how we found the truth about where our genus Homo came from—and where it evolved.

Tool use marks a tremendously important step in evolution. But how important is it really, considering chimpanzees can also make and use tools? Professor Martin offers you a detailed picture of what early stone toolmakers were like, as well as some of the primitive tools found in parts of Africa.

Examine what the fossil record reveals about Homo habilis, a species that serves as a transitional marker between Australopithecines and the rest of the genus Homo. A key mystery in this lecture: how Homo habilis can have the anatomy to be our ancestor yet not exist at the right time in evolutionary history.

Using a magnificent find of the skeleton of a 1.5-million-year-old boy (known as the Nariokotome skeleton), delve into the issue of how important size was to becoming human. Recent discoveries of Homo erectus remains, as you’ll discover, have led to a reevaluation of the growth process of these hunters and gatherers.

Professor Hawks explains the complexities of the Movius Line, a fairly clear line that separates the Western distribution of hand axes from areas in the East where they were rarely made. Central to this constant puzzler in the story of evolution are the more than 500,000-year-old remains of the Peking Man.

The identity of Homo floresiensis, a species of small-brained humans that averaged a height of 3.5 feet, is the most burning debate in paleoanthropology. Investigate the origins of these mysterious “hobbits” and whether they represented a new species of human or were merely the remains of abnormally developed modern humans.

12. Archaeology and Cooperation

Explore what archaeology tells us about cooperation and compassion in prehistoric people with this insightful lecture. Professor Hawks reveals how archaeological remains and other kinds of evidence offer intriguing clues about how prehistoric people worked together to make tools, hunt animals, share meals, and even take care of their injured.

13. Presapiens or Preneandertal?

Working with the European fossil record, examine the debate over whether Neandertals were our true ancestors, or simply a much less specialized population. Along the way, you’ll comb through remains from Spanish caves in Atapuerca and encounter the notorious evolutionary forgery known as the Piltdown Man.

French archaeologist Francois Bordes interpreted variations in stone tool remains as evidence of different groups of people who existed in the past. American archaeologist Lewis Binford, however, believed these variations reflected different activities. Who was right? Find out in this lecture on the way scientists interpret the archaeological record.

15. Did Neandertals Speak?

How important was language to shaping human evolution? Discover the answer to this question by studying the skeletal remains of Neandertals discovered in the late 20th century. Learn how anthropologists, with the help of a specific bone and a key language gene, determined that Neandertals could—contrary to earlier beliefs—talk.

16. Neandertals—Extinct or Ancestors?

Follow along as scientists examine Neandertal genes to determine just how close our ties are to this primitive species, which disappeared about 30,000 years ago. What scientists found when the entire genome sequence of Neandertals was reconstructed in 2010—and what it reveals about the true fate of Neandertals—may surprise you.

17. Is Our Neandertal Heritage Important?

Are there behaviors we can trace back to our Neandertal heritage by closely studying mitochondrial DNA? If so, what’s useful? What isn’t? It’s a debate nearly as old as anthropology itself—and Professor Hawks’s explanation of how it works forms the subject of this provocative and insightful lecture.

Did modern humans emerge from Africa? Or did they evolve in regions around the world? These two competing questions became the most persistent debate in anthropology in the late 20th century. Consider evidence for either scenario and learn how scientists reached their current understanding of the dispersal of modern humans.

Investigate the important role of climate change events—specifically the catastrophic eruption of Mount Toba around 74,000 years ago—in shaping the rise of man. Did this event cause a population crash among prehistoric humans, finishing off some populations and paving the way for the spread of modern humanity?

20. Language—Adaptation or Spandrel?

For decades, scientists debated over whether language was a target of natural selection in evolution or merely a side effect. Blending anthropology and linguistics, Professor Hawks helps you make sense of what Charles Darwin, Noam Chomsky, and others had to say about evolution’s role in the development of human language.

Is prehistoric art just a side-effect of our intelligence, or is it somehow fundamental to our cultural abilities? Explore this perplexing question by closely examining beads, utilitarian tools, decorative objects, rock art, and other primitive art forms unearthed at archaeological sites in Europe, Africa, and Australia.

Professor Hawks discusses the continuing debate over the arrival of humans in the New World. Some anthropologists believe that the Clovis culture was the first to spread south across North America about 12,000 years ago. Others believe there may have been even earlier migrations to the Americas.

In this lecture, investigate the relationship between agriculture and the spread of early human societies throughout Europe. Central to this is the argument over whether agriculture spread through population movements into widespread areas, or whether adjacent populations simply adopted farming practices (as well as new languages) without mass migration.

To conclude the course, Professor Hawks addresses some of 21st-century anthropology’s most important questions. Are we still evolving? Is human evolution slowing down or speeding up? What are we going to look like in the future? And is it possible for us to actually bring evolution under our control?

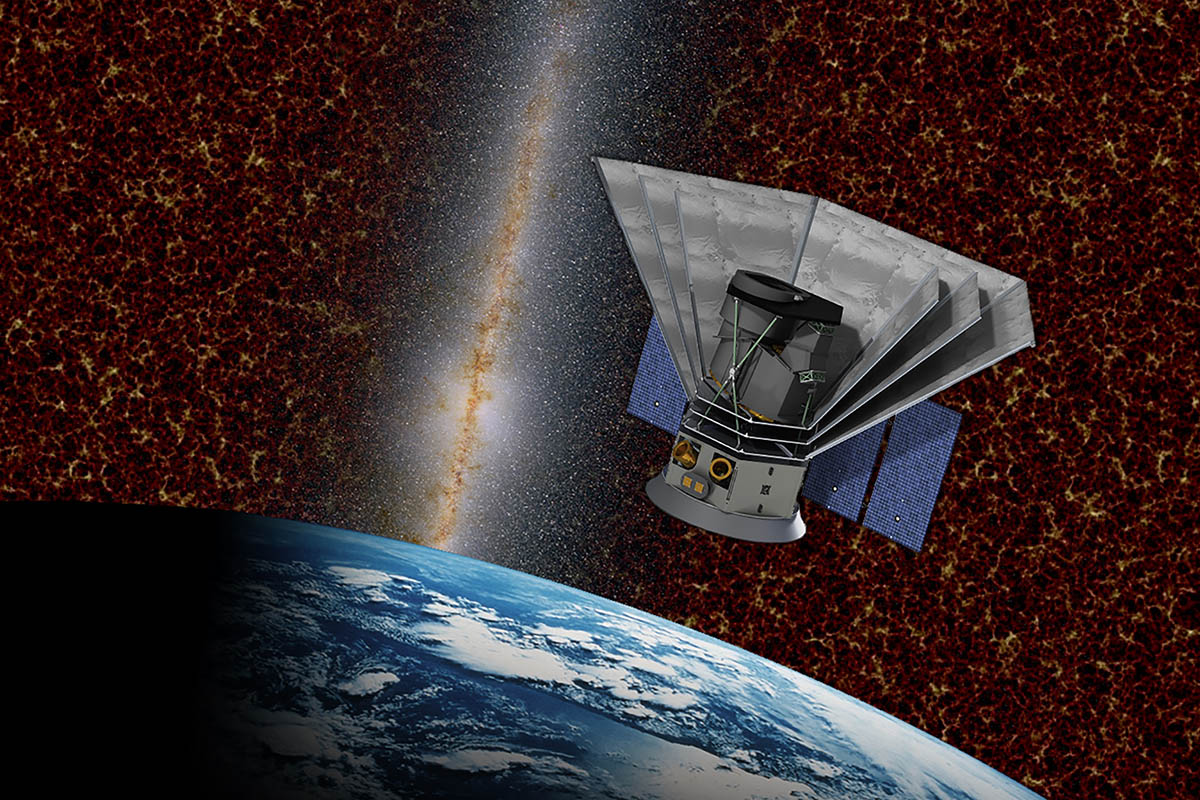

Big History, The Big Bang, Life on Earth and the Rise of Humanity

Big History, The Big Bang, Life on Earth and the Rise of Humanity

Biological Anthropology: An Evolutionary Perspective

Biological Anthropology: An Evolutionary Perspective

What Darwin Didn’t Know: The Modern Science of Evolution

What Darwin Didn’t Know: The Modern Science of Evolution

Major Transitions in Evolution

Major Transitions in Evolution

Understanding the Human Body: An Introduction to Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding the Human Body: An Introduction to Anatomy and Physiology

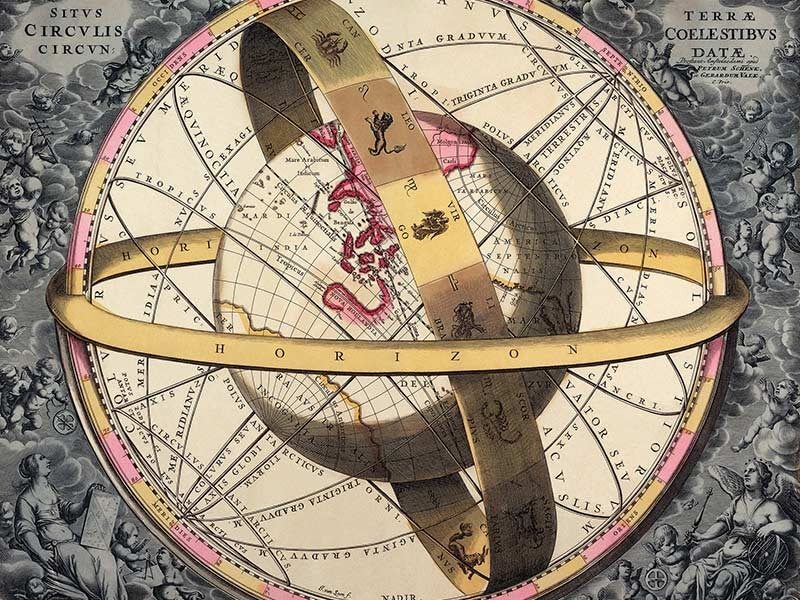

History of Science: Antiquity to 1700

History of Science: Antiquity to 1700