description:

When we consider ourselves, not as static beings fixed in time but as dynamic, ever-changing creatures, our viewpoint of human history becomes different and captivating.

episodes:

01. What is Biological Anthropology?

Whether studying primates in the field, gene sequences in a lab, fossils from the Earth, or modern human populations across the globe, biological anthropologists employ an evolutionary perspective to understand the history of our species, and perhaps its future.

02. How Evolution Works

Evolution, or systematic change in a gene pool over time, is driven by the mechanisms of natural selection, mutation, gene flow, and genetic drift. Understanding the role played by “differential productive success” helps us to see that evolution still plays an important role in our lives today.

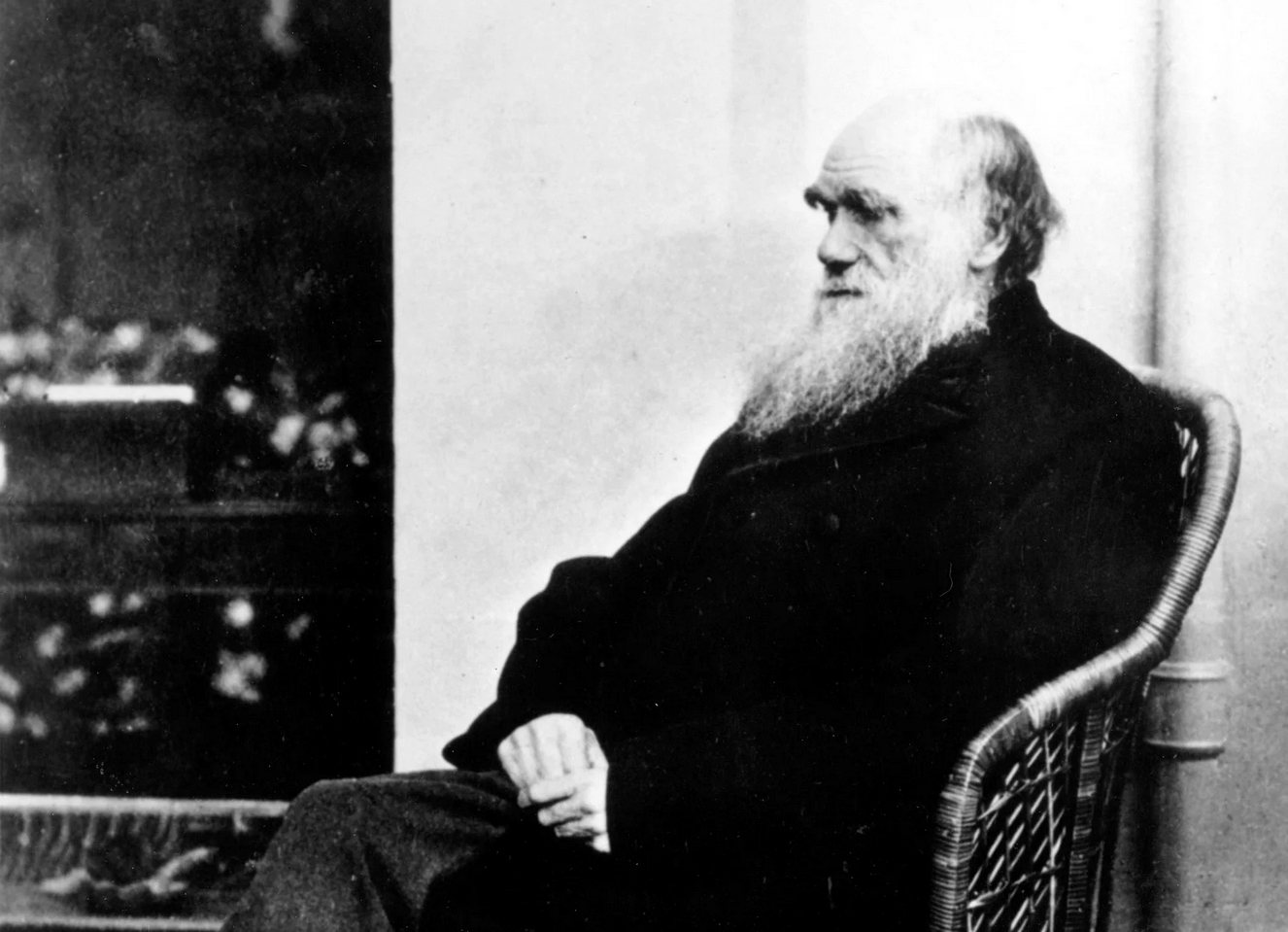

03. The Debate Over Evolution

Americans continue to reject the theory of evolution in large numbers, perhaps because of a perceived incompatibility between belief in evolution and religious faith. In fact, some evolutionary scientists are deeply religious. Scientific creationism, however, and even the newer doctrine of intelligent design, are fundamentally at odds with the bedrock principles of biological anthropology, and of science itself.

04. Matter Arising—New Species

As different animal populations become isolated from each other, differing selection pressures cause them to adapt to their ecological niche, until a variety of forms emerge which cannot interbreed. About 65 million years ago, ancestral rodent-like populations underwent such pressures, resulting in the emergence of primates.

05. Prosimians, Monkeys, and Apes

The obvious anatomical and behavioral differences among these three subgroups of non-human primates led early anthropologists to focus on their static measurement and classification. In 1951, Sherwood Washburn focused on how the dynamic processes of evolutionary change had produced different yet fundamentally related species.

06. Monkey and Ape Social Behavior

The rhesus monkeys of Cayo Santiago, an island off Puerto Rico, organize their society around groups of differently ranked females, while chimpanzee communities are male-dominated, organized around communal male hunting and border patrols. As Washburn would have predicted, a common trend of hierarchical grouping and intense social bonding emerges, across diverse primates.

07. The Mind of the Great Ape

Is there a watershed difference in cognitive abilities between great apes and other non-human primates? Advocates of this viewpoint point to two phenomena: the great ape’s “theory of mind,” or its ability to comprehend another being’s mental state, and the great ape’s ability to communicate through gestures and human-devised symbol systems.

08. Models for Human Ancestors?

Some anthropologists create models for the evolution of human behavior by studying primates whose behaviors most closely resemble our own. Others say we should only study behavior shared universally by all great apes. Some stress that the process by which a behavior emerged in a primate group can best indicate how our own behaviors evolved.

09. Introducing the Hominids

The hominids are the first human ancestors, diverging from a common ancestor with the great apes some six or seven million years ago. Despite fossil evidence and the contributions of molecular science, the precise speciation date is still elusive. Climate change and dietary pressures are examined as possible explanations for the hominids’ key anatomical adaptation, bipedality.

10. Lucy and Company

When the 40 percent complete Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) skeleton was found in 1974, she upset researchers’ expectations by being bipedal, yet possessing an ape-sized brain. Subsequent studies of other species show us that a variety of bipedal hominid forms had evolved even earlier than Lucy, and that they co-existed. Rather than a straight line, evolution more resembled a many-branched bush.

11. Stones and Bones

Homo habilis, who first appeared 2.4 million years ago, was not the first gracile, light-boned hominid, but it was the first to leave evidence of its lifestyle. It manufactured rudimentary stone tools, probably used to forage and to process animal carcasses. Different cultural practices have been inferred from this tool use, but the technological leap it represents is certain.

12. Out of Africa

With Homo erectus, some hominid populations migrated from their African homes and into Asia. Anatomical advantages of this species included a larger brain, and in the case of an African specimen, a tropically adapted body frame. Its more advanced toolkit allowed more efficient animal processing, while its probable control of fire aided hunting, cooking, defense, and temperature control.

13. Who Were the Neandertals?

In 1911, a French anatomist fashioned a reconstruction of a Neandertal based on a skeleton afflicted with arthritis, and the stooped, shambling, primitive figure that resulted has lived on in the popular imagination. In truth, Neandertals were large-brained, upright bipeds, effective hunters, and sophisticated toolmakers. Their practice of deliberately burying their dead hints at a possible symbolic dimension.

14. Did Hunting Make Us Human?

Intelligence and the ability to cooperate are essential to success in hunting. Could these qualities have been naturally selected, and acted as prime evolutionary movers in the evolution of human intelligence? Critics note that there is little evidence for hunting in many of the early hominids, while others stress that social coordination and problem solving are equally required in female gathering activities.

15. The Prehistory of Gender

The prehistoric landscape of behavioral gender differences is a veritable minefield, where an anthropologist’s inferences may always fall prey to ideology. From the 1960s until today, we have seen models that promote the male as the protector and provider, making no allowances for behavioral flexibility. Alternatives that posit the primacy of female-centered networks in place of the nuclear family are no less constraining.

16. Modern Human Anatomy and Behavior

Unlike bones, modern human behavior cannot easily be dated. The famous Lascaux cave paintings, together with other artifacts from Western Europe, were once thought to be firsts. New excavations of rock art and finely worked tools in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, and Namibia are challenging this view, and showcase Africa once more as the likely crucible of progress.

17. On the Origins of Homo sapiens

Did modern Homo sapiens evolve entirely on the African continent, then fan out into Asia and Europe, replacing other hominid forms as they went? Or would it be more accurate to see evolution from intermediate hominid forms occurring simultaneously, and in the same direction, on all three continents? Fossils, knowledge of evolution, and genetic testing all contribute to theories, but no single answer has yet been reached.

18. Language

With its immense vocabulary and complex syntax, modern language is often seen as a mysterious development, lying on the far side of some mist-shrouded Rubicon from which the point of origin is barely visible. This need not be so. Anthropologist Robbins Burling has proposed a scenario that includes the step-by-step evolutionary shifts necessary to get us from ape communication to human language.

19. Do Human Races Exist?

To quote anthropologist Michael Blakey, the idea that people can be grouped into races may seem as obvious to us as the sun rising in the east. Blakey’s point, however, was that our eyes can mislead us, and common sense can be inadequate to deal with scientific questions. This lecture confronts the question of whether skin color or other attributes can be used to sort people into biologically meaningful categories.

20. Modern Human Variation

If race is a flawed prism through which to view human diversity, how ought we to understand it? A population that undergoes pronounced selection pressures may experience significant evolutionary changes. This lecture considers the anatomical adaptations that occur in response to extreme climates, as well as the process of acclimatization, a non-genetic type of human adaptation.

21. Body Fat, Diet, and Obesity

Humans developed the ability to convert calories into fat deposits to combat the periodic food shortages endemic to early hominid life. Consequently, we are not well adapted to process large portions of salt, sugar, and fat. Anthropologists propose various ways of coping with this adaptation to the past.

22. The Body and Mind Evolving

Recent research suggests that morning sickness in pregnant women, and hypertension in African-Americans, can be explained in evolutionary terms. By considering psychology and even moral action as similarly influenced by evolutionary pressures, are we at risk of endorsing biological determinism?

23. Tyranny of the Gene?

The disappointing results of animal cloning confirm that environment plays as great a role as genes do in an organism’s biological destiny. Understanding how genes affect human health may produce promising treatments, but we affirm the fundamental truth that genetic material acts, and is acted upon, in complex and unpredictable ways.

24. Evolution and Our Future

Even though Homo sapiens is now the planet’s dominant species and prime evolutionary mover, the selection pressures we generate and are subject to will have consequences that we cannot predict. The intimate connection we share with our primate relatives and all other animal species should inspire a sense of common responsibility as we meet the challenges of the future.